By Christina Fattore | September 7, 2018

The announcement last month that the U.S. and Mexico had reached an agreement to replace NAFTA without Canada surprised trade experts around the globe. A deadline of Aug. 31 was set for the Canadians to join or be left out in the cold – and hit with fresh tariffs.

The news was stunning because negotiators for all three countries had been trying to hammer out a new accord for over a year, ever since President Donald Trump followed through on his campaign threat to demand the North American Free Trade Agreement be scrapped or replaced.

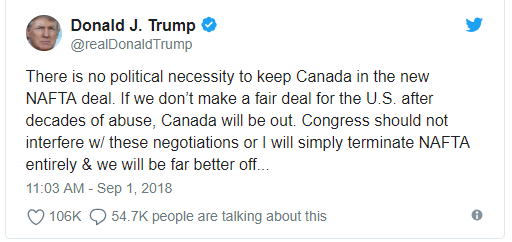

After the arbitrary deadline passed without any concessions from the Canadians, let alone a finalized deal, Trump once again threatened to exclude Canada from the new NAFTA via Twitter.

While his blustering included a threat to end NAFTA entirely, it is all bark and no bite. What trade scholars like me know is that Trump does not have the upper hand in these negotiations.

Interest groups on both sides of the border will ensure that Canada is in the deal – and legally, it would be cumbersome to do a deal that excludes the Canadians.

Interest groups usually win

In his tweets, Trump claimed that there was “no political necessity to keep Canada in the new NAFTA deal.” However, Canada does not seem to be feeling any sense of impending doom – and for good reason.

After Trump’s threats, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said a compromise “will hinge on whether there is ultimately a good deal for Canada. No NAFTA deal is better than a bad NAFTA deal.”

In my own research I’ve studied how interest groups influence trade policy, specifically in World Trade Organization dispute initiation and litigation. My work illustrates how countries depend upon industry interest groups – and in some cases, companies themselves – to help shape trade policy.

This research borrows from the work of Princeton politics professor Andrew Moravcsik, who theorized that countries – especially democratic ones – primarily represent the preferences of domestic interest groups when engaged in international negotiations, and will rarely kowtow to the desires of trading partners.

In other words, governments want to stay in power and get re-elected. They need votes and campaign contributions to meet that goal, and corporate and industry interest groups can provide both.

That’s why Trudeau continues to stand firm that any deal with the U.S. and Mexico protect Canadian middle class jobs by protecting domestic dairy and poultry production and why he insists a so-called cultural exemption that safeguards domestic television and radio from takeovers by U.S. media conglomerates be included in the new NAFTA.

Trudeau and his team of negotiators are not going to sing to the tune of Trump’s tweets. Rather, they’re following the standard political economist playbook: protect those industries and sectors that can help carry Trudeau to another win in the federal elections 13 months from now.

Americans first

On the other side of the table, there’s Trump.

He professes to have American interests at heart in his hard-line handling of Canada in these ongoing NAFTA negotiations. And he has framed NAFTA as a disaster and an agreement that has brought “the U.S. … decades of abuse” at the hands of Canada.

What Trump hesitates to acknowledge is the interdependence between the U.S. and Canadian economies. Both countries need each other.

Canada is the United States’ second-largest trading partner, with US$673 billion in total goods and services crossing the border in 2017. The U.S. Department of Commerce estimates that exports to Canada support over 1.5 million jobs, heavily concentrated in border states that went for Trump in the 2016 presidential election.

Take the automobile industry as an example: If Canada was left out of NAFTA, car prices could rise in the U.S. due to proposed new tariffs on Canadian autos. And Canadians are already discussing a boycott of American goods if negotiations turn sour, which could also lead to a decline in the sales of American cars.

If consumers in Canada and other countries are buying fewer American cars as a result of these trade disputes, that could lead to layoffs. The possible downward spiral that could result has both the auto industry and labor unions concerned about a NAFTA with no Canada.

And it’s not just cars. If Canada is kicked out of the new NAFTA, Americans would see a number of industries negatively affected, from oil production to retail stores to tourism as Canadians will choose to buy more domestic products to avoid American ones.

Basically, a NAFTA without Canada is a lose-lose situation for all involved. And while Trump may be willing to ignore the wishes of some interest groups since he has two years before he faces re-election, most lawmakers in Congress don’t have that luxury as the midterms fast approach.

It’s hard for me to imagine that Congress would support a NAFTA minus Canada, regardless of who controls the House in January 2019.

Three is not a crowd

The idea of throwing NAFTA out all together is, in my view, ludicrous, as industry on both sides of the border will not stand for it and Congress will not support it.

Trump is also legally restricted. While he has been granted fast-track authority by Congress to renegotiate NAFTA, this only allows Trump to ask lawmakers to approve a deal, by an up or down vote, that includes all three countries. If the current negotiations fail and Trump presents Congress with a trade deal with Mexico alone, the process will be slow and could be held up significantly – especially if there’s a change in control of the House.

Considering manufacturing interests were pro-NAFTA in 1994 and continues to derive benefits from the treaty today, North Americans can expect whatever replaces that deal to continue with Canada well into the future regardless of how long these negotiations take.![]()

Christina Fattore, Associate Professor of Political Science, West Virginia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.