Bill Anastasiou / Shutterstock.com

By Dimitrios Syrrakos | August 20, 2018

After nine years of unprecedented peacetime economic hardship, Greece exits its IMF bailout programme on August 20. So ends a series of three bailouts organised by the so-called troika of the IMF, European Central Bank and European Commission. A total of €336 billion was lent to Greece in the wake of the financial crisis, to stop it defaulting on its national debt, with approximately €300 billion used so far.

What’s more, over 90% of the funds were not directed toward investment projects, but went on servicing Greece’s national debt. And the financial aid was provided on the basis of severe cuts to spending – a harsh regime of austerity.

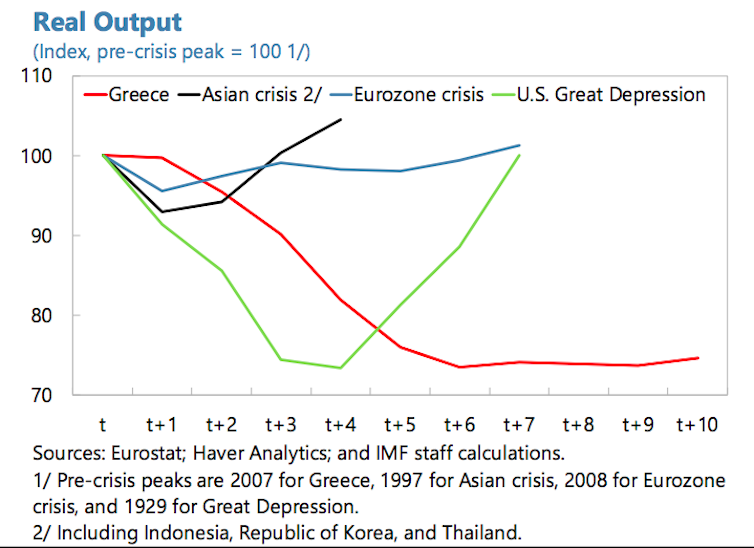

It had tragic results. A quarter of Greece’s 2009 economic output has been wiped out, 20% of its workforce is out of work, and youth unemployment is at about 40%. At the height of the crisis, in 2014-15, unemployment reached a staggering 27%, with youth unemployment exceeding 50%.

The strict nature, implementation and dramatic social costs of the EU bailouts prompt questions about their effectiveness – and whether they should be used in the future. Greece suffered the most. But bailouts, with strict conditions and severe consequences were meted out to Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Cyprus. The exact nature of the bailouts differed in each country, but they all shared the same draconian nature and rationale.

The IMF, which helped with Greece’s bailout loans, has since admitted that it underestimated the negative effects that austerity would have and the scale of the recession that would ensue. But this is not enough.

Blame game

The repercussions of the bailouts raise a core question. Whether the eurozone debt crisis was caused by the fiscal profligacy of the countries that were crisis-stricken and needed bailing out? Or whether it was down to deeper issues with the eurozone system as a whole?

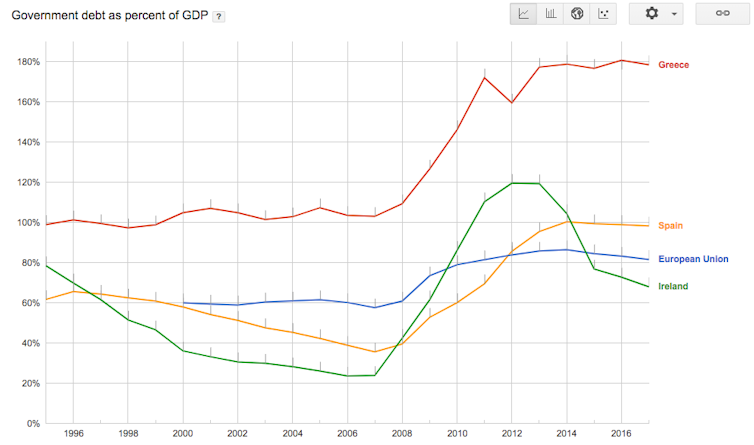

There is no concrete answer to this fundamental question. Many observers focus on the aspects of the crisis that fit their particular narrative. For example, there is no doubt Greece and Portugal had overspent for decades before 2010. But politicians in the eurozone’s north focused entirely on fiscal profligacy when assessing the causes of overspending.

Other factors – such as consistently higher military expenditure than the EU average in Greece; the country’s unique geography, which includes 2,000 islands of which 200 are inhabited; the lack of an industrial base, and a political system based on a clientele relationship between the state and its citizens – were completely ignored. For politicians in the fiscally prudent north of the eurozone, tax avoidance and overspending was more than enough to justify the bailouts.

But fiscal laxity was far from the norm in Spain and Ireland. Both countries had very low debt-to-GDP ratios up to 2008 (considerably lower than the EU Maastricht Treaty’s 60% limit) and yet they were subjected to the same draconian bailout provisions.

Some critics of the bailout perceive the crisis to be primarily institutional and so oppose the punishing measures that came with them across the board. They claim that had the European Central Bank acted decisively in 2010 by introducing quantitative easing, the extent of the required cuts would have been significantly reduced, thanks to the extra liquidity.

And despite Greece’s obvious need for extra liquidity from 2010-15, it was the only eurozone country to be excluded from the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing policy from 2015-18. The ECB’s intervention in 2010 could have mitigated the effects of the cuts and ultimately made the recession less severe, as was the case in Ireland and Portugal.

The way forward

Somehow, the eurozone has survived the experience of the bailouts and remains intact. But the lack of consensus over the causes of the crisis makes it difficult for the eurozone to move forward in the best way possible.

Alongside a central fiscal authority to oversee the budgets of all eurozone countries (in effect, a eurozone finance ministry that would take considerable time and effort to establish as it would have to aggregate national preferences over taxation and spending), the eurozone urgently needs a complete banking union to prevent future crises. This would involve a pan-eurozone deposit guarantee scheme. Had such a scheme existed in 2008, depositors would not have had the incentive to move their assets from one eurozone country to another when the crisis hit, thereby exacerbating it.

Attempts to create such a union over the last five years have stalled. Eurozone countries like Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and Finland want depositors to participate in bank bailouts, as in the case of Cyprus in 2013, as a means of preventing the need to nationalise banks and their liabilities. The authorities in these countries fear that it would be their taxpayers that would be called upon to bail out banks in southern eurozone countries, in particular Italy where economic crisis looms.

This is a perfectly rationale argument. But so is the southern eurozone authorities’ point, that it is very difficult to maintain sufficient liquidity in their banking sectors in the absence of such a banking union, as the mere suspicion of financial difficulty or political instability could precipitate abrupt and massive flows of capital out of their countries. Hence the current deadlock.

Yet a banking union is the best way to boost confidence in the eurozone and make it less prone to economic shocks that it may find difficult to withstand, let alone to absorb. Greece has taught us this much.

Dimitrios Syrrakos, Deputy Head – Department of Economics, Policy and International Business, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester Metropolitan University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.