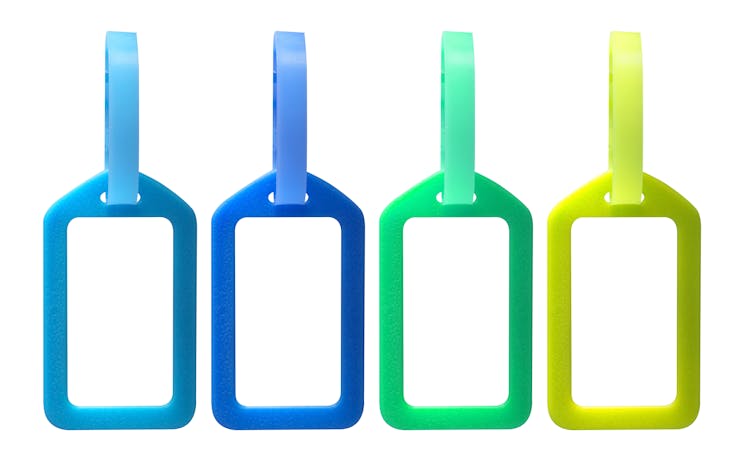

There’s no such thing as a free luggage tag. Chatcharin Sombutpinyo/Shutterstock.com

By Jonathan Meer | November 2, 2018

You’ve almost certainly opened an envelope containing a solicitation from a nonprofit and discovered a set of mailing labels with your name and address on them. Or a few bookmarks with the group’s branding. Or, just as likely, the offer of a mug, a tote bag or some other gift in exchange for your donation.

I get a few of these “tokens of appreciation,” known as donor premiums, every month. About 60 percent of American nonprofit solicitations for support include them upfront or dangle them as a reward for giving.

But why do charities give stuff away when they ask you for money? I am an economist who studies altruism and philanthropy. The prevalence of this fundraising mainstay sparked my curiosity. Clearly, charities think this kind of swag inspires people to give, but I wanted to find out whether they work and, if so, how.

Enticement or wasteful obligation?

Expert opinion and scholarly evidence on the effectiveness of donor premiums is mixed. Some nonprofit professionals claim that donors expect and want these premiums. Others point to surveys in which donors say would prefer that the group they’re supporting spend as much of their donation as possible on their work and not waste their money on trinkets.

Other economists who have researched this question have generally found that donor premiums do tend to induce more giving, but they are rarely cost-effective.

Along with other researchers, I have previously detected a strong distaste among donors for premiums as they can add to overhead, administrative and fundraising costs – potentially making people less motivated to give to a cause they support.

Together with my colleague Catherine Eckel at Texas A&M University and David Herberich, who is a vice president at Marqeta, a payment platform, I partnered with the Texas A&M alumni association to unpack how donor premiums work.

Tag, you’re it

If donors are driven by a need to give back, we hypothesized, they might be inclined to give more in response to a higher-quality gift sent to them unconditionally. But if they dislike overhead costs, pricier gifts might reduce their giving.

If it’s the thought that counts, we figured, then just offering a gift that’s conditional upon a donation should have the same effect as an unconditional gift received no matter what. And if donors have the opportunity to decline or opt into receiving premiums in exchange for donations, we believe that would signal whether they really want to maximize the charity’s funding – by turning them down – or if they really do desire the item.

With the help of our research partner, we mailed about 140,000 alumni one of seven different solicitation letters.

A control group received no gift offer. One group got a leather A&M-branded luggage tag in the mailing requesting a donation while another group received a plastic luggage tag.

Four groups received a conditional offer: a luggage tag in response to their donation. One group merely received the offer. Another group had an identical solicitation with related wording on the outside of the envelope. This tested whether prospective donors could be made more likely to open the mailing. The other two had the option to decline the tag or, to ensure our phrasing wasn’t driving the results, the option of receiving it.

What works?

Several months after the letters went out, we compared donation rates in response to the different letters.

Only 0.49 percent of the people in the control group donated in response to the premium-free solicitation. While it may seem quite low, that response rate is not unusual for direct mail.

Adding the plastic luggage tag as an unconditional donor premium increased the donation rate slightly, to 0.60 percent. The leather luggage tag group had a substantially higher response rate of 1.02 percent.

Those differences suggests that some sense of reciprocity – a donor’s perceived need to respond to the charity’s gift – does drive giving and that donors are responsive to higher-quality gifts. Aversion to overhead costs, that is, doesn’t completely undo the effectiveness of premiums in getting donors to give.

The four groups offered conditional gifts all donated at about the same rate as those in the control group. What that means is that a premium that’s mailed in response to a donation does not have the same impact as a “front-end” premium, at least in the context of these fundraising letters.

Those donors who did give in the conditional variations showed strong preference for receiving the luggage tags. When they had to make an active decision to receive the tag, 61 percent chose to get it while 88 percent chose not to opt out of receiving the tag. This suggests that many donors are not motivated by the desire to maximize the impact of their donation.

Unconditional swag

So unconditional premiums might be popular with donors – but do they help nonprofits raise money?

Not by a long shot. While donors gave the most in response to the leather luggage tag they got just for being asked to give, that trinket was much more expensive than the plastic tags. Including mailing costs, each solicitation actually cost US$2.87. Even though they didn’t raise as much, the plastic tags did better as a fundraising tool because they weren’t as pricey. But, on net, they still lost $0.59 per mailed letter.

Meanwhile, the solicitations that offered plastic tags in response to a gift raised an average of 40 cents each, net of cost – a sum that is statistically indistinguishable from the average of 39 cents collected in response to mailings that included and promised no premiums at all.

Fans of using premiums to raise money for causes believe that they are worth it even if they simply get donors in the door but do not raise more money than giving them away costs charities. That’s because, at least theoretically, they can form a habit of giving. But some researchers have found that donors who are lured into giving by donor premiums are unlikely to give again when asked without an incentive.

What should nonprofits and donors take away from our study? We conducted this experiment with just one organization, but the preponderance of the evidence from our work and the findings of others suggests that unconditional premiums are not worth it.

These trinkets may have been a good idea when they were novel and unusual, a few decades ago. But they are so common now that many donors probably don’t even notice them.![]()

Jonathan Meer, Professor of Economics, Texas A&M University