By Anand Menon, and Matthew Bevington | November 28, 2018

Economic perceptions matter. Polling expert John Curtice has shown that expectations of economic impact shape preferences around Brexit. As many as 96% of Remain voters think the UK will be worse off after Brexit, and would consequently vote Remain if given another chance. For Leave voters, 94% think the UK will be better off and would vote to leave again. So knowing what might happen matters.

According to the government’s latest analysis, Brexit will mean UK growth is slower than if it hadn’t voted to leave. The Treasury report did not forecast the impact of the Brexit deal that’s on the table, but the modelling suggests it would reduce UK GDP by 2-4% in the next 15 years. If there is a no-deal Brexit, the UK economy could shrink by 9.3%.

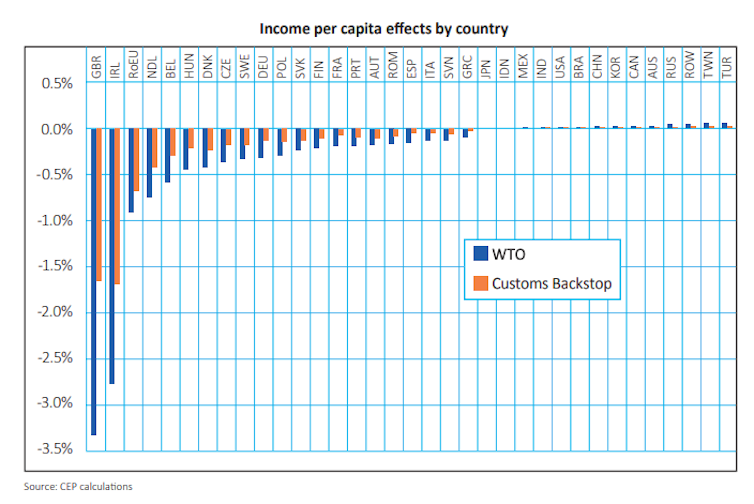

We at The UK in a Changing Europe, working with the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, have reached similar findings, modelling specifically for how the prime minister’s Brexit deal would affect the UK economy.

We estimate that Theresa May’s deal could reduce UK GDP per capita by between 1.9% and 5.5% over ten years, compared to the “baseline” scenario of remaining in the EU. The cost to the public finances would be between 0.4% and 1.8% of GDP over the same period, and the corresponding figures for a no-deal Brexit would be 1% to 3.1%.

This is difficult to put in perspective, but a 0.4% hit to the public finances implies about £9 billion less in tax receipts by 2030 and a 3.1% fall suggests something of the magnitude of £64 billion. And this accounts for the repatriation of UK contributions to the EU budget and ignores any short-term disruption that might arise when the UK first moves to new trading terms.

Let’s try to put this into comparative context. The IFS estimates that the financial crisis cost the UK economy £300 billion in the decade since 2008. Our modelling implies lost output of between £40 billion and £110 billion by 2030. Brexit would therefore be substantially less damaging than the financial crisis. This being said, however, it comes on top of a decade of lost growth at a time when the country is less well placed to cope.

An informed estimate

We should stress of course that our results are subject to a high degree of uncertainty. This is partly a result of difficulties inherent to economic modelling. It is also partly down to the vague and aspirational language in the political declaration on the future relationship between the EU and UK. We’ve had to make some fairly big assumptions about what this might mean in practice. Specifically, there is insufficient detail in the withdrawal agreement to know exactly how the customs backstop would operate or the extent of future regulatory divergence between the UK and the EU.

All this being said, these findings represent our best judgement about the impact of the deal. That does not mean they will be correct – indeed, they almost certainly will be inaccurate to some extent. But they do provide an informed estimate of what might happen.

Ultimately, there are some basic facts that need to be acknowledged if we’re to have a sensible public debate about what Brexit will mean. It is not possible to have frictionless trade with the EU without also having the legal obligations that enforce such lack of friction. If it were, there would frankly be little value to being in the EU in the first place.

UK in a changing Europe

Nor is it possible to maintain the economic benefits of such frictionless trade with our nearest and largest trading partner from the outside. Furthermore, as our modelling of a substantial reduction of immigration in the research also shows, we cannot severely limit immigration without bearing an economic cost for it. Politicians are well within their rights to make a policy choice to reduce immigration, but they ought to acknowledge the cost of doing so.

None of this is to say, of course, that there aren’t legitimate counter arguments. Economics isn’t everything. Moreover, there are those who would argue that aggregate measures of the state of the national economy have little bearing on their own lives and livelihoods. It might also be the case that the economic impacts will be slow to materialise, so voters might not directly notice any changes, and any they do notice might not necessarily be attributed to Brexit. In other words, the economics could ultimately turn out to be irrelevant to the politics.

It is fine to argue that Brexit is worth the economic damage it implies, that economics is not the most important consideration, or that economic warnings are overblown. What is not acceptable is to deny that there will be any damage at all.![]()

Anand Menon, Professor of European Politics and Foreign Affairs, King’s College London and Matthew Bevington, Researcher, UK in a Changing Europe, King’s College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.